Dear Reader,

Sometimes the work we do for ourselves finds its way out into the world. That’s what happened this month to me. I’ve written poetry for as long as I can remember. I was lucky enough to grow up around lots of old books, as my parents and grandparents kept stacks of them around. I vividly remember turning over those glorious, stiff pages and reading old Victorian poetry aloud. I tried writing it, rhyming stanzas based on the old verses I read, comparing myself to Wordsworth and Longfellow.

Thanks to high school and college creative writing classes, I learned that modern poetry didn’t need to rhyme, so I filled my journals with the stuff, in between entries. It was historical fiction novels I really wanted to write though, so for the most part my poetry was a secret pleasure just for me.

When I moved to Astoria, I found a group that had been meeting for years to read poetry aloud to each other once a month. I began attending, and while my greatest focus will likely always be prose, the act of regularly writing poetry and reading it in community has had a cumulative impact. Over the past few years, I have see my work improve as I’ve written more of it. I gained a better sense of how a listening audience reacts to a line, and taking workshops from Pacific Northwest poets has helped me grow as both a poet and a writer. (Thanks here to Kim Stafford, John Sibley Williams, Neil Aitken, Jericho Brown, Brenda Cárdenas, and the poets at Ric’s Open Mic).

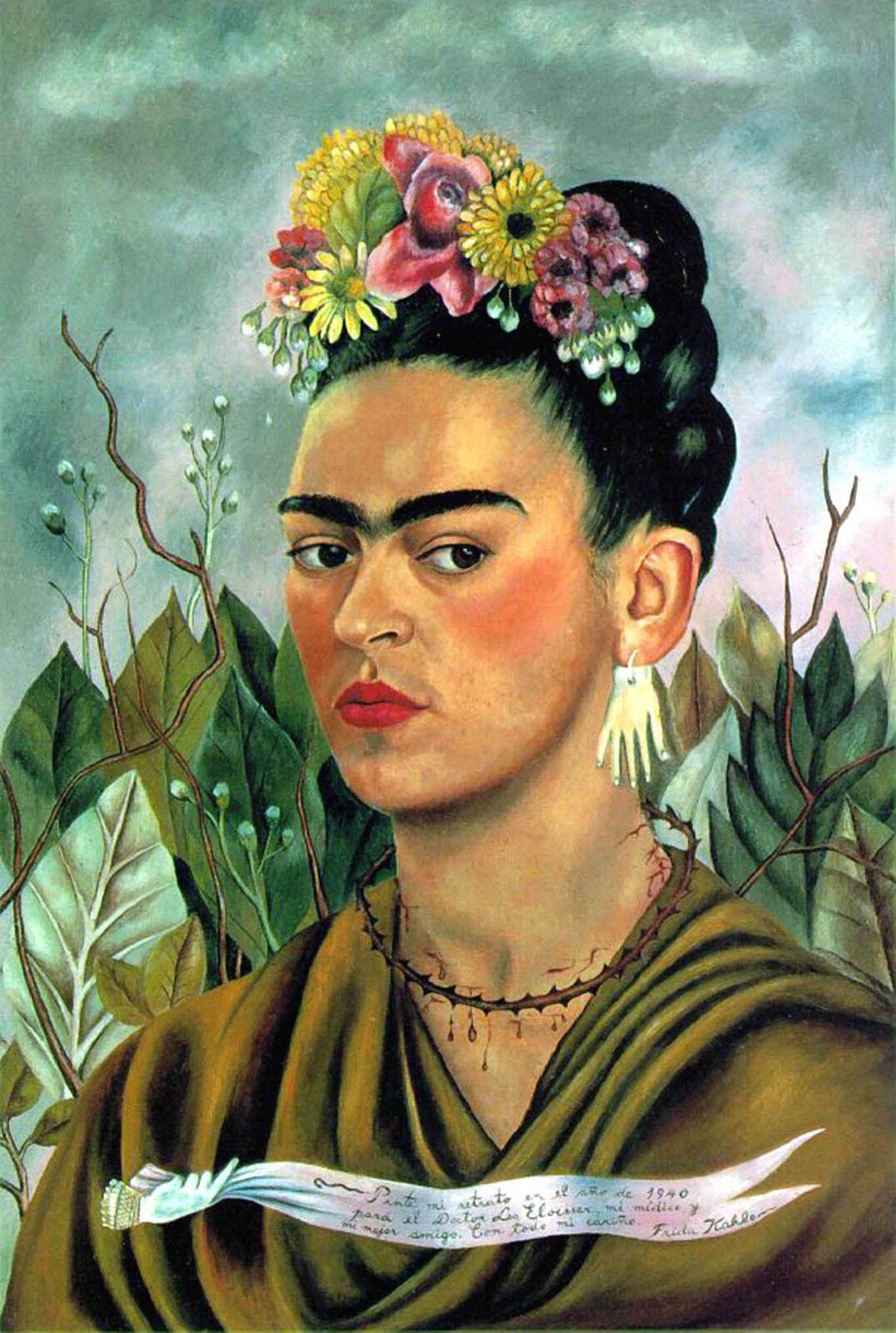

While doing research about the great Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, I came across some contemporary press reactions to her work. Journalists, predictably, mainly focused on her husband, Diego Rivera, an immensely talented Mexican muralist. Of Kahlo, they glibly said things along the lines of: “Oh, his wife likes to dabble around with paint too. How cute.”

Seeing Kahlo’s work trivialized by her contemporaries in this way filled me with rage. There was a complete lack of understanding about the incredible strength Kahlo had to endure the challenges of her life and still create in the midst of such pain. I recognized a familiar tone that “Important” critics often take as they regard the creative work of women—dismissive, infantilizing, with an utter lack of respect for the artistry, brilliance, and complexity that is present in the work.

From this place of rage and profound respect for Kahlo’s life and work, I wrote a poem about her. The result was Stillicide, a word I coined to encapsulate the silencing of her contributions.

I am thrilled and honored that this month the poem earned second place in the 2024 Hoffman Center for the Arts’ Neahkanie Mountain Poetry Prize. I’ll be reading it along with the other award winners at a poetry celebration Sunday April 14th at 4 pm at the Hoffman Center in Manzanita, Oregon. If you’re in the area, please join us!

Here is what judge Logan Garner said about Stillicide:

“Frida Kahlo has never been so visible and fully-formed to me as she is now, after having spent significant time with Stillicide. This poem celebrates her personhood well beyond her life as a means to producing works of art, an otherwise-common tendency of historical summaries. The narrator of Stillicide evokes with such intimacy a life fraught with illness, poverty, tragedy, personal and political strife, and a sense of self made to balance on a knife’s edge between cultures and eras, even life and death. Short of reading a singularly poetic biography, this poem does well to bring something of Frida’s soul to this reader.”

Stillicide

By Marianne Monson

Little Frida Magdalena Carmen,

How preciously you paint on uneven legs

dabbling so sweetly with spider monkeys and parrots

Playing out your bloody fantasies,

the pink of your painkillers, the orange of overdose,

the leg amputations and gangrenous toes

How darling, adorable of you

to trace La Llorona, murderer of children.

For, of failed abortions and miscarriages

How much can you know?

Of a pelvis impaled by a handrail of iron,

Of corsets fashioned from plaster and steel?

You, satin ribbon wrapped round a bomb,

You, dove chained in marriage to an elephant,

whose night trysts with your sister bring

children to dandle on your knee

Delicate mestiza flower,

What can you know of art, trapped there behind an easel

strapped to your bed in La Casa Azul?

Where you peer in that mirror,

at a life lived while dying,

dipping brushes into peasant clothing—

huipils, rebozos and Aztecan legends

Paint with your own eyes and nothing more, my dearest darling

Sketch skeletons and black angels to watch

from the length of your four poster bed

Use paint as a pain killer, oh precious one.

And when you are gone, we will bury you sweetly

beneath a girlish flag of communist red

Dear Reader, may the work you do in secret, for your own soul, find its way out into the world.

Love,

Marianne

Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait 1940

The universe is funny and timely! I’ve been studying Frida Kahlo for the last couple of months. Her work in relation to plants and her garden at Casa Azul are part of my work for Papernoten right now.

This poem’s tone does such a nice job of capturing her strength and determination.