“A raw, brilliant account of war that may well serve as a final exorcism for one of the most painful passages in American history…it’s not a book so much as a deployment, and you will not return unaltered.” -Sebastian Junger, The New York Times

Dear Reader,

I am sitting alone in a quiet, brooding house, weeping into a pillow as my cat tries solicitously to comfort me. She does not understand that I am weeping for children who died in a jungle far away and long ago, a few years before I was born.

The quote above by Sebastian Junger was excerpted from his review of the novel Matterhorn, by Karl Marlantes, a decorated Marine who served in Vietnam and wrote about his war experiences in the 600-page missive that has captured my waking thoughts and returns at night to haunt my dreams.

In many ways, Vietnam is a war I’ve known little about, at times intentionally. I was born in 1975, only a few months before Saigon fell, and I remember my father telling me that despite his high school athletic prowess, he’d avoided the draft because he enrolled at Harvard. While I’ve wanted to watch the documentary by Ken Burns, I’ve avoided it, knowing the emotional toll on someone as sensitive as I am will be heavy. The closest I’ve come to engaging with the war was as a traveler in Vietnam, where I spent hours in the Saigon war museum, and even crawled through an actual tunnel once used by the Viet Cong. I passed people on the streets of Ho Chih Mihn city whose faces had been disfigured by Agent Orange, a chemical weapon whose impact is passed down genetically within families, an ongoing reminder of a war most would like to forget. As a traveler, I learned about the war from the Vietnamese perspective, a humbling glimpse for an American into the other side of the story.

Matterhorn is the first time I’ve delved into the war from the perspective of the Marines who were sent halfway around the world to stop the invasion of the corrupt South Vietnamese government by the communist North Vietnamese in the face of decaying support from the local population and growing condemnation from communities at home, who were horrified by the costs of war televised for the first time. The justifiable outrage at the war was all too often misdirected toward U.S. soldiers, who Marlantes refers to as “kids” throughout the book, a subtle reminder that far too many of those dying in pursuit of this nebulous objective hadn’t even spent twenty years on this planet.

Before reading this book, I knew nothing of jungle rot. I didn’t know about immersion foot or the leeches soldiers encountered. I had not realized they had to worry about attacks from tigers. I did not know that five U.S. servicemen killed in Vietnam were sixteen years old and one was fifteen.

I cannot speak of the impact of this book on veterans. I would imagine that the visceral descriptions of battle and warfare could potentially flare PTSD symptoms. I can, however, speak to the impact of the book on someone who personally loves several veterans. Both of my grandfather served in World War Two, and the battle scenes in the novel give me a glimpse into what those years must have been like for them, my paternal grandfather in the Italian alps combatting a similar enemy under similarly horrific conditions in a very different climate, with perhaps a greater sense of purpose about the work he was doing. My son is scheduled to discharge from the National Guard in a few short months having served the terms of his contract while having never seen active combat. Many of the tears I have been shedding have been imagining this beloved son of mine contending with an enemy in a jungle, struggling days without food and water, watching friends blown into unrecognizable pieces around him. I am crying for relief that it seems he has avoided this reality and for the guilt I feel knowing other people’s beloved sons and loved ones have not been as lucky.

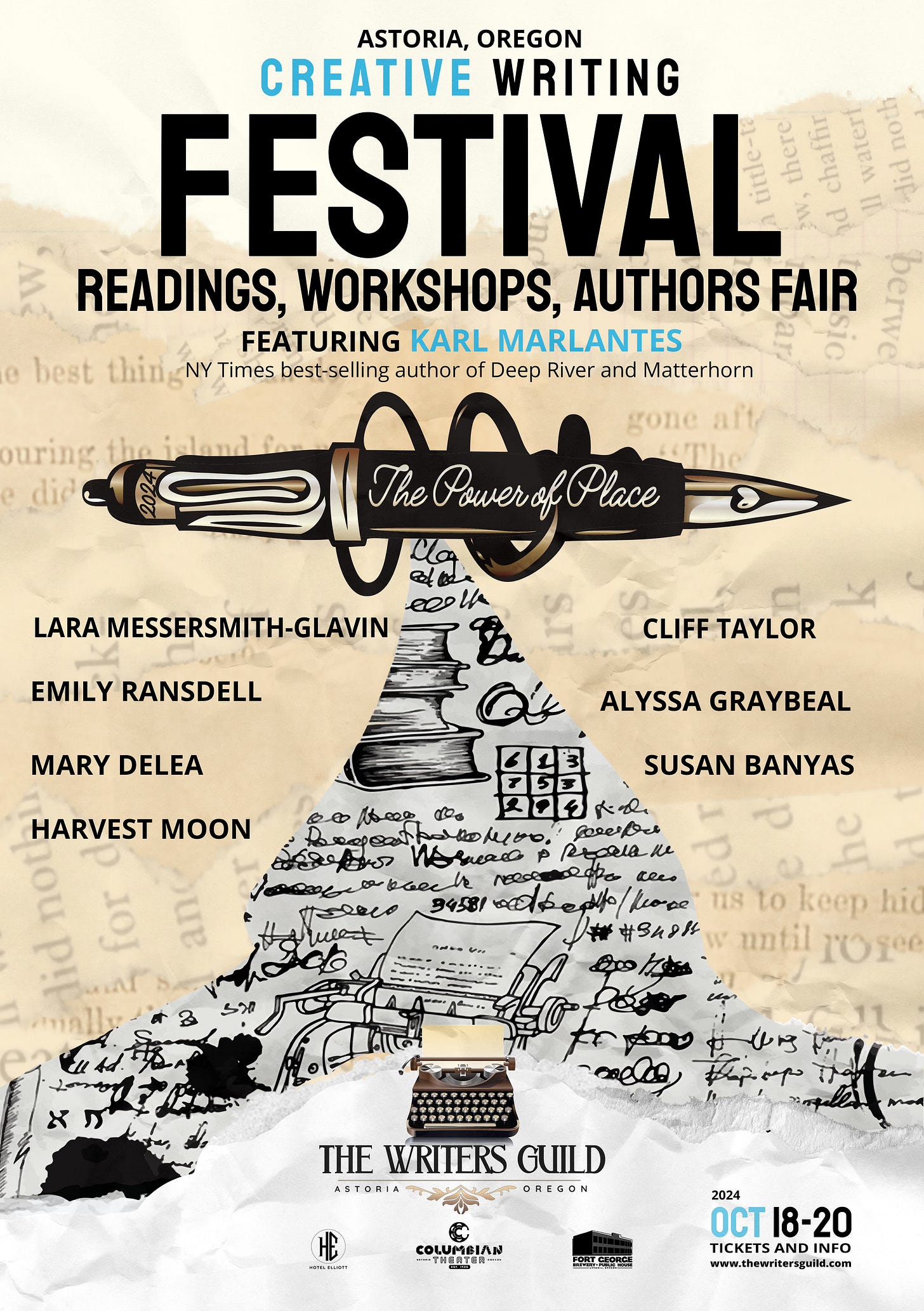

I am reading Matterhorn because in October, I will have the privilege and honor to interview Karl Marlantes on the stage of the beautiful Liberty Theater in Astoria, Oregon. I had originally planned to focus mainly on Deep River, a brilliant historical fiction novel about the Finnish immigrants who settled the areas of the lower Columbia, but after reading Matterhorn, I know we’re going to have to divide our time between the books (and that’s not even saving some time for his newest release, Cold Victory).

The interview is one part of a weekend long Creative Writing Festival that literary arts nonprofit, The Writers Guild, has been working on for more than a year. Marlantes is the keynote speaker, and he will offer a writing workshop for participants (something he has rarely done before). Beyond Marlantes, there’s an incredible line up of performers and writers sharing their art and expertise. If you’re a reader (or a writer) within travel distance of Astoria, I highly suggest joining us October 18-20th. It is shaping up to be an unforgettable weekend, and you still have time to read at least one of Marlantes’ missives before asking him to sign it.

As a women’s history author, I am accustomed to analyzing the way women are exploited by society—for their sexuality, their reproductive labor, and their emotional labor. Yet, Matterhorn has me thinking deeply about the ways men are exploited by our same society for their physical labor, for their protective instincts, as they are asked to bear the emotional and psychological toll of our nation’s killing, of our insatiable drive for economic growth regardless of costs.

Beyond gender, all of us suffer the cost of exploitation; we lose collectively when nations engage in violence. 2,709,918 Americans served in Vietnam. 58,148 were killed in Vietnam; 75,000 were severely disabled; 5,283 lost limbs; 1,081 sustained multiple amputations. 1 million civilians were killed. Millions more were impacted because they loved people who were killed or wounded. The environmental impact of the war caused permanent and irreversible damage to the Vietnamese landscape, causing several species of animals and vegetation to become extinct. Ironically and tragically, the war ultimately only damaged the U.S. economy and weakened military morale.

The lessons from Vietnam have in other ways been long-lasting. My son was safer during his service because of those “kids” we lost in the jungle. As the years progress, World War two veterans like my grandfather are dwindling rapidly. The Vietnam veterans are a few decades behind them, but eventually they too will be gone. This October is a rare opportunity to hear from one of those particularly eloquent veterans speak about his service. I hope to see you there.

Love,

Marianne

Excellent post, Marianne. Matterhorn is fascinating - a 600-page page turner. There but for the grace of God might have been I. I was two years too young for the draft. I thank my lucky stars.